DEEP DIVE: Online grocery series: The UK – a battle for profitability

KEY POINTS

This is the first in our series of reports analyzing online grocery markets around the world. Here, we focus on the UK, a world-leading market in Internet grocery retailing.

- Competition in the UK online grocery market intensified in June due to the entrance of AmazonFresh. Amazon will likely steal grocery share from the big four traditional retailers and from Internet pure play Ocado.

- E-commerce grocery logistics are complex and expensive. The costs of fulfilling online orders are likely to further erode grocers’ operating margins, which are already razor-thin. Online grocery businesses struggle to turn a profit.

- UK grocers are trying to balance online sales growth with profitability by increasing minimum basket sizes for free delivery and by nudging customers toward the click-and-collect option.

- While the established major chains may all sense that they must pay more attention to profitability, newcomer AmazonFresh is expected to make it tough for the incumbents to focus on profitability and maintain online market share.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The UK is the most developed online grocery market in the world. Brits spent £9.8 billion buying groceries online in 2015, an increase of 13% year over year, according to research firm Mintel. However, even in this comparatively well-developed market, online sales represented only 6% of total grocery sales of £163 billion. As at June 2016, some 6.9% of all sales of fast-moving consumer goods (FMCGs) were online, according to Kantar Worldpanel.

Mintel expects UK online grocery sales to grow at a five-year compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9% and reach £15 billion by 2020.

We think the disparity between the substantial numbers of people shopping online and e-grocery’s still-minor share of total grocery sales suggests opportunities for sustained and substantial gains in share: with a large number of Brits now buying groceries online, the market can be grown by increasing their frequency of purchase.

Data from research firms suggest that the online channel is increasing its share of the UK grocery market at roughly one percentage point every two years. From this, we estimate e-commerce will be capturing around 9% of the market in 2020.

The prospects for growth may look impressive, but grocery is a large, nondiscretionary category, so the vast majority of grocery e-commerce will be diverted from the traditional brick-and-mortar channel: there will be virtually no net top-line gain for the overall grocery sector.

A notable feature of the UK e-grocery sector is the dominance of retailers from the brick-and-mortar world. The UK’s “big four” grocery retailers with online business are Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons. Ocado is the country’s only grocery Internet pure play retailer of significant scale.

The arrival of AmazonFresh in the UK in June 2016 has only intensified the competition. We believe Amazon will progressively steal grocery market share from the big four UK traditional retailers—Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons—as well as from pure-play grocery retailer Ocado. Incumbent grocery retailers have already undertaken some initiatives to better position themselves to compete with the Amazon.

Grocery retailers are under pressure to provide faster click-and-collect and delivery options at more stores, all while charging customers lower fees for doing so. While e-grocery is a high-growth channel, it poses challenges to brick-and-mortar grocery retailers due to its less-profitable or even unprofitable nature.

Complex e-commerce logistics and the incremental labor and transportation costs associated with picking and delivering orders place further cost burdens on these retailers, eroding operating margins that are already razor-thin.

In response, some grocers are now focusing on better balancing online sales growth with profitability. However, this renewed focus on profitability coincides with the arrival of AmazonFresh, and we think the incumbents will find it tough to both concentrate on profitability and hold market share when faced with such a sophisticated and aggressive new competitor as Amazon.

INTRODUCTION

This is the first report in our series on grocery e-commerce, which will analyze online grocery retailing across different markets. In this report, we begin by examining the size of the UK market, its forecast growth rate and the proportion of UK grocery sales that are generated online.

We then turn to the online businesses of the UK’s “big four” grocery retailers—Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Morrisons—and to Ocado, the country’s only grocery Internet pure play. We discuss the competitive dynamics in the sector and the numerous challenges grocery retailers are facing.

In addition, we examine the recent UK entrance of AmazonFresh, how the incumbent grocery retailers are positioned and the steps they have taken to grow their respective online businesses.

Finally, we look at the critical issue of profitability. Online grocers face declining profitability due to the competitive pressures of faster order assembly and delivery, which could negatively impact operating margins as online grocery continues to grow.

UK ONLINE SALES TO CONTINUE STRONG GROWTH TREND

We begin with an overview of the market’s size and growth prospects. The UK is the most developed online grocery market in the West, as confirmed by data from a number of market-measurement firms.

At June 2016, some 6.9% of all UK sales of FMCGs were online, according to Kantar Worldpanel. This puts the UK well ahead of any other Western markets.

Data from research firms including Kantar Worldpanel and Mintel suggest that online is increasing its share of the UK grocery market at roughly one percentage point every two years. From this, we estimate e-commerce will be capturing around 9% of the market in 2020.

According to Mintel:

- The UK online grocery market grew by 13% year over year, to £9.8 billion in 2015.

- Online sales represented only 6% of total UK grocery sales of £163 billion last year.

- UK online grocery sales are expected to grow at a five-year CAGR of 9% and to reach £15 billion by 2020.

- As of December 2015, 48% of UK Internet users surveyed by Mintel said they had shopped online for groceries in the last 12 months. Approximately 11% of Brits do all their grocery shopping online and a further 12% do most of it online.

We think the disparity between the substantial numbers of people shopping online and e-grocery’s still-minor share of total grocery sales suggests opportunities for sustained and substantial gains in share: with a large number of Brits now buying groceries online, the market can be grown by increasing their frequency of purchase.

Euromonitor International expects online sales of food and beverage categories to grow at a five-year CAGR of 6.6% to reach £6.2 billion in 2020, up from £4.5 billion in 2015. This looks like a conservative forecast, given the double-digit growth rates for online grocery in the recent past and the forecast from Mintel, noted above.

The prospects for growth may look impressive, but grocery is a large, nondiscretionary category, so the vast majority of grocery e-commerce will be diverted from the traditional brick-and-mortar channel: there will be virtually no net top-line gain for the overall grocery sector.

A strong e-commerce offering is no longer simply an option for nondiscount, big-basket-focused grocery retailers; it is a requirement. And competitive pressures within the channel are increasing as speed and convenience are becoming more important to maintaining customer loyalty in the online grocery market.

UK ONLINE SECTOR: BRICK-AND-MORTAR NAMES LEAD IN E-COMMERCE

A notable feature of the UK e-grocery sector is the dominance of retailers from the brick-and-mortar world. Tesco is the UK market leader in online grocery sales, with approximately 39.1% market share, according to 2014 data (latest) from Mintel. This is greater even than Tesco’s share of overall grocery sales (offline as well as online), which was 28.1% in mid-2016, according to market measurement firm Kantar Worldpanel.

Tesco is followed by Sainsbury’s, which holds a 17.5% share of the online grocery market, according to Mintel. Ocado is the only grocery pure play of any scale, and it held a 13.4% share of the online sector in 2014, tying for third place with Asda. However, given Asda’s overall underperformance since 2014, and that Ocado has tended to grow faster than the total e-grocery market, we suspect Ocado has moved ahead of Asda by now.

Morrisons was late to move online, launching its e-grocery service only in 2013 under a deal with Ocado through which the pure play would provide its online service. As a result, Morrisons holds a marginal online market share that is substantially lower than its overall grocery share.

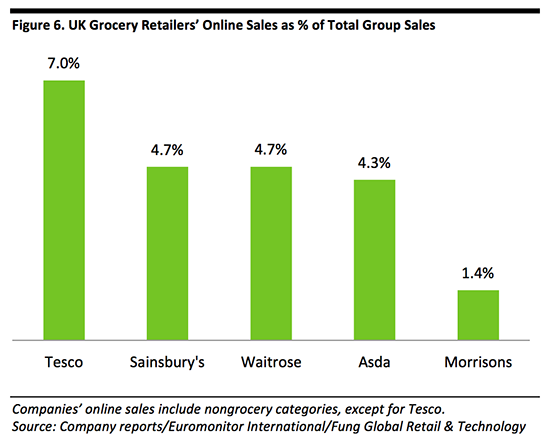

The figures below show selected major retailers’ online and offline market share positions, as well as their absolute online sales and online sales as a percentage of total group sales.

Of the retailers shown below, The Co-operative Food, Aldi and Lidl do not sell online. The high added costs of Internet grocery retailing fit poorly with the low-cost, no-frills model of the discounters. Meanwhile, Co-op Food is predominantly a convenience-store operation, and small basket sizes and impulse purchases do not suit online shopping.

The graph below shows selected grocery retailers’ total online sales, including nongrocery categories such as apparel and electronics.

According to Tesco’s most recent earnings call transcript, online grocery sales represent approximately 7% of the company’s total sales, amounting to £2.6 billion; this figure does not include the retailer’s sizable general merchandise e-commerce operation.

Tesco moved online early in the UK, launching an online shopping service in 1997. This helps explain its high share of e-commerce relative to its peers.

SUPERMARKETS CHALLENGED ON ALL FRONTS

In this section, we place grocery e-commerce in context—and it is one of sector upheaval. UK grocers are facing multiple challenges, including low margins, the rise of discounters and consequent strong price competition, and the entrance of retail giant Amazon into the market.

The Discounters Have Reshaped How Grocery Is Sold…

Offline, the surge of the no-frills discounters has been the defining battle in UK grocery since the 2008 economic downturn. The top four UK supermarket chains continue to struggle to stem their share losses to German discounters Aldi and Lidl. Kantar Worldpanel measures individual UK grocery retailers’ sales every 12 weeks and, in its latest update, for the period ended September 11, the firm recorded sales declines for Asda, Sainsbury’s, Tesco and Morrisons. Meanwhile, Aldi grew sales by 11.6% and Lidl by 9.5%. Aldi and Lidl have grown their combined UK market share to about 10% since the recession.

…and Prompted Margin-Depleting Price Competition

Overcapacity in brick-and-mortar stores and the rapid growth of the discounters have resulted in much stronger price competition, which, in turn, has hit the margins of nondiscount grocery retailers. Morrisons has been cutting prices on hundreds of products, Sainsbury’s recently completed its shift to an everyday low price strategy and Asda recently announced average price cuts of 15% on more than 1,000 products.

UK grocery sales are expected to remain subdued due to continued food deflation resulting from price wars and the discounters’ increasing market share. At (2.0)%, UK grocery price deflation is reaching record levels, according to the UK’s Office for National Statistics.

The situation was reflected in Ocado’s recent, third-quarter 2016 trading statement, in which it noted that the UK grocery market remains very competitive, with sustained and continuing margin pressure. Ocado reported that its average basket value had declined by 3.4% year over year, to £107.94, impacted by price deflation. It is clear that if such negative trends continue, UK grocery retailer margins will erode further.

Future Competition

Online, UK grocers are also likely seeing some loss of share to restaurant food delivery and takeout entrants such as Just Eat, UberEATS, Amazon Restaurants and Deliveroo. These online aggregators and apps make it much easier for consumers to find and buy food from the fragmented restaurant sector, and we think some of that sector’s growing share is coming at the expense of grocery retailers.

Offline, mixed-goods discount retailers such as Poundland and B&M provide further price-led competition. The UK’s biggest mixed-goods discounters, which include B&M, Home Bargains, Poundland, Poundstretcher and Poundworld, generate the majority of their sales from grocery categories.

These retailers sold around £3.6 billion of food and beverages, health and beauty products, and household FMCGs in 2015, we estimate. We further estimate that this total grew by approximately £2.1 billion, or more than 140%, in five years.

- For more data and analysis, see our UK’s Second Grocery Discount Boom report from December 2015 at bit.ly/FungUKDiscount.

At the same time, FMCG and consumer-packaged goods brand owners, including Reckitt Benckiser, Unilever and Diageo, are experimenting with online distribution on demand and with subscription services that offer automatic replenishment. Some of these companies are venturing into direct-to-consumer distribution that cuts out the retailer completely:

- Reckitt Benckiser has established a new global e-business unit to deal with customers such as Amazon and Alibaba.

- Unilever recently purchased online subscription shaving products retailer Dollar Shave Club for US$1 billion.

- UK spirits manufacturer Diageo recently made an investment in Drizly, a US startup that delivers beer, wine and spirits on demand.

AMAZON’S ENTRY INTO THE UK GROCERY MARKET

The launch of Amazon’s online grocery service, AmazonFresh, in the UK will increase competition and customer expectations even more. It will also force incumbent UK grocery retailers to invest more capital in their online businesses, which will further squeeze profit margins.

Expanding on its existing Amazon Pantry offer, which is an online grocery store selling non-fresh groceries and household products, Amazon introduced AmazonFresh in the UK on June 9, 2016. The service offers more than 15,000 items, including fresh food, perishables and household staples from brands such as Coca-Cola, Kellogg’s and Danone.

Amazon also secured a deal with Morrisons to supply fresh and packaged private-label products. In addition, products from more than 50 of London’s premium local producers, shops and markets are available. The AmazonFresh service is available only for subscribers to Amazon Prime, which costs £79 per year in the UK. Prime members pay an additional £6.99 a month for AmazonFresh.

Amazon offers same-day delivery for most orders, and one-hour delivery in some areas in Greater London. One-hour delivery slots are available from 7 am–11 pm, seven days a week, while same-day delivery is available from 5 pm–11 pm for orders placed by 1 pm. Deliveries made within two hours do not incur additional costs. Amazon does not operate its own delivery trucks for AmazonFresh; it relies on independent transport partners such as couriers who make deliveries using temperature-controlled packaging.

Amazon has also introduced home inventory replenishment and reorder solutions, such as the Amazon Dash wand, to encourage repeat purchases, increase grocery and staples shopping frequency on Amazon’s platform, and grow purchase basket size. Amazon Dash is a one-click Internet-of-Things wand that enables shoppers to add items to their AmazonFresh cart from home; users either scan the barcode of a product with the wand or simply say the name of the product while holding the device.

The company is working on automating the Dash service entirely, so that appliances such as printers, vacuum cleaners and washing machines order new ink, bags and detergent automatically when supplies run low. Bosch, Siemens, Samsung and Whirlpool are among the companies already collaborating on integrating the Dash Replenishment Service into their products.

WHAT ARE GROCERS DOING TO EXPAND THEIR ONLINE BUSINESSES TO COMPETE WITH EACH OTHER AND COUNTER AMAZON?

The major UK grocery players had been competing for share among themselves, but now that they face the prospect of competing against online giant Amazon, they have undertaken some initiatives to better position themselves to compete with the newcomer.

Sainsbury’s

Sainsbury’s has just opened its first stand-alone fulfillment center for online orders and trial same-day delivery. The company currently fulfills online orders from its supermarkets and the new facility will add capacity for 25,000 more orders per week. Sainsbury’s had previously announced plans to double its click-and-collect locations and trial same-day click-and-collect.

The company is now preparing to roll out same-day grocery deliveries from 30 stores and is already testing same-day deliveries at three stores in Central and South East London. Sainsbury’s is also testing a new app that promises one-hour delivery within a three-kilometer radius of a store. Shoppers can order up to 20 items and pay £4.99 for one-hour delivery.

Tesco

Tesco introduced same-day grocery click-and-collect in 300 stores on August 24. Shoppers can collect their purchases three hours after placing an order, so an order placed before 1 pm can be picked up after 4 pm the same day. For deliveries, Tesco charges £2 for those made Monday to Thursday and £3 for those made on Friday and Saturday. The company does not deliver on Sundays.

Asda

Asda initially opened collection points in universities, business parks and transportation stations as well as drive-through collection points at its own stores. In November 2013, the company announced an expansion of click-and-collect services and said it planned to open 1,000 click-and-collect points in the UK by 2018. However, the company decided last year to slow the expansion and instead invest in improvements to its brick-and-mortar stores, apparently to protect profitability. Asda is owned by US-based retailer Walmart and is incorporated as a privately held subsidiary in the UK, so there is much less publicly available information on the company’s online business relative to its publicly listed peers.

Morrisons

In May 2013, Morrisons signed a 25-year partnership with Ocado to launch its online grocery business, and the first deliveries were made in 2014. Ocado provides Morrisons with its technology services, warehouse space, staff and delivery vehicles (vehicles used for the Morrisons businessare branded with Morrisons logos).

Morrisons recently renegotiated its deal with Ocado, which will expand its capacity for online retailing even further. The entry of Amazon seems to have given Morrisons some leverage in renegotiating its agreement with Ocado at more favorable terms. Ocado will develop a store picking solution for Morrisons, and Morrisons will take space at Ocado’s new customer fulfillment center, which will open in 2018 and be able to process more than 200,000 orders a week.

Additionally, the new contract will enable Morrisons to break free from an exclusivity arrangement that prevented it from picking orders from its own stores in areas that could not be reached by Ocado’s delivery fleet (Ocado has only about 75% geographic coverage of the UK). Hence, under the new agreement, Morrisons will be able to reach 100% of the UK market. Morrisons will also sell Ocado’s nonfood items, thereby broadening its online product offering.

In terms of contract economics, Morrisons is now paying less investment capital up front and keeping more of its future online profits than it was able to under its initial agreement with Ocado. Morrisons will receive a discount on the research and development fees it has paid since 2014 and also be released from a profit-sharing agreement that dictated it pay Ocado 25%–50% of profits once Morrisons’ online business reaches profitability.

The new contract also forbids Ocado from entering into similar technology partnerships with Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Lidl and Aldi. However, it will now take longer for Morrisons’ online business to reach profitability than the company had originally planned.

Ocado

Ocado has stated that it has not witnessed any impact from Amazon entering the UK grocery market. According to Ocado’s CFO, AmazonFresh’s growth in Europe is advantageous to Ocado, as it will help grow the overall online grocery market. Ocado believes that there is room in the market for both companies to continue to grow and create more channel shift.

Ocado has been operating same-day delivery for the last eight years or so, but only in a small number of regions. The company’s CEO has said that the majority of orders are delivered the next day and that Ocado continues to expand its same-day delivery service. As the company grows and opens more warehouse facilities, it will be able to make more same-day deliveries, as more customers will live in the vicinity of a nearby facility. Two new warehouses set to start operating in 2017 and 2018 aim to increase store pick rates even further. Ocado will continue to pursue lapsed customers and those most likely to become active loyal customers through focused marketing efforts.

ONLINE BUSINESSES ARE NOT AS PROFITABLE

While e-grocery is a high-growth channel, it poses challenges to brick-and-mortar grocery retailers due to its less-profitable or even unprofitable nature.

The grocery industry has competed away the cost of delivery and, from the retailer’s perspective, e-commerce is not an opportunity, but an expensive, profit-curbing necessity.

E-grocery is less profitable than in-store retailing because grocers have to pick, pack and deliver goods for a relatively small fee. For example, it costs £10–£12 to pick and deliver an online grocery order, according to Shore Capital stockbrokers cited on Bloomberg in June 2016. Yet our spot checks for this report suggest that major UK grocers are charging just £0–£7 for deliveries, with the higher rate being a relative rarity.

So, online grocery retailing for traditional grocers is not considered a profit center, but a necessity—because customers demand it. Ocado has even stated that traditional grocery retailers do not really want to sell online because store sales are more profitable, but that they have to have a presence online. Furthermore, e-grocery is a key means by which traditional grocers can battle the rise of the German discounters; the discounters have no online grocery businesses and are very unlikely to launch them in the medium term, given the mismatch between their no-frills business models and the added costs of online grocery retailing.

E-commerce significantly increases operating costs, especially in terms of providing same-day home delivery, which is the highest-cost option. UK grocers initially launched their e-commerce services using costly fleets of delivery trucks, but they are now expanding more cost-effective click-and-collect services. Grocers already have very, very low operating margins, ranging from 1.2% at Tesco to 3.7% at Waitrose, and the costs of fulfilling online orders are likely to hit margins at most e-grocery retailers.

Fees for click-and-collect and home delivery have generally been declining with increased competition. And online grocery retailing currently seems to be less profitable than brick-and-mortar retailing due to the labor costs associated with product picking and delivery. Traditional grocers pick most online orders from their stores, using existing resources, as this makes logistical and operational sense, and some are building more dark stores to facilitate online order fulfillment.

Grocery retailers are reticent about sharing online profitability and online delivery margin figures. The majority of analysts assume e-grocery businesses are loss making.

- Morrisons has stated that its online business is still not profitable, although losses are decreasing and the company expects its online EBIT loss to continue to decline each year.Tesco has stated that its online business is still profitable, but less so on a like-for-like basis than it was a few years ago, particularly because the market has competed away the cost of delivery. Moreover, Tesco picks most of its grocery orders in its existing stores, which means it may be accounting for the costs of its online grocery service on an incremental-cost basis only.

- Ocado has barely registered a profit since being listed on the stock market in 2010 and it did not report its first net profit until 2014. The company continues to be barely profitable; its fiscal year 2015 net profit margin was 0.01%.

After several years of chasing online sales growth at the expense of the bottom line, British grocery retailers are now trying to balance e-commerce growth with profitability. On its most recent earnings call, covering the first quarter of 2016, Tesco stated that it is less willing to subsidize online operations and that its online sales growth has actually been decelerating quite significantly. Tesco is focusing on balancing online sales growth with long-term profitability by increasing the basket size requirement to qualify for low delivery prices, increasing delivery prices, and decreasing promotional and unique offers online.

Sainsbury’s has stated that it has seen some early signs of rationality in the market in terms of grocers not just chasing online promotional sales through vouchering, but also focusing on channel profitability.

However, this renewed focus on profitability coincides with the arrival of AmazonFresh, and we think the incumbents will find it tough to both concentrate on profitability and hold market share when faced with such a sophisticated and aggressive new competitor.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Shoppers’ increasing demands for convenience and speedy delivery and pickup have intensified the competitive dynamics in the UK online grocery channel.

- The arrival of AmazonFresh in June 2016 has also intensified the competition and resulted in a race to provide free click-and-collect and same-day delivery services.

- After years of chasing top-line growth and competing on reducing the fees charged to shoppers, major UK grocery retailers are finally paying more attention to the issue of reduced profitability resulting from the high labor costs associated with picking and delivering orders.

- While the established major chains appear to have realized that they must pay more attention to profitability, they have done so just as AmazonFresh has arrived on UK shores. The newcomer is expected to make it tough for the incumbent online players to both focus on profitability and maintain their online market share.